A week or two ago “mobile virtualization” provider RedBend created a bit of press announcing their vLogix Mobile 5.0, which they claim is much faster to integrate than other solutions. (If you look at what architectures are supported, you know why: they target only ARM Cotex-A15 and Cortex-A7 cores, which are the ones with hardware virtualization support. Sure if you don’t para-virtualize things go faster. Have a look at our evaluation of ARM’s hardware support for virtualization with the first hypervisor that supports it).

So far, so boring. They also make claims that their mobile virtualization solution is deployed more widely than all the others concerned, a somewhat amusing statement, given that to date not a single product has been publicly identified that uses RedBend virtualization! If so many use it, why don’t they own up?

What most surprised me when looking at their web site is that they still have an optional isolator module. Does this sound familiar? Well, that’s exactly what VirtuaLogix (which RedBend bought in Sep’10) had! I had examined this in detail 4 years ago and pointed out that isolation of virtual machines is an inherent consequence of virtualization, not an optional add-on. What was behind is that VirtualLogix used a pseudo-virtualization approach which runs guest OSes in privileged mode, at the same privilege level as the hypervisor. Their optional “isolation mode” meant de-privileging the guest, exactly what the rest of the world calls “virtualization”.

I find this all a bit dishonest. In fact, if we were talking about a consumer product sold in Australia, I would ask the Dept of Fair Trading whether this might constitute misleading advertising…

Also, I would have thought that they would have learned how to do it properly in the meantime. Reading the description of the “optional isolator” on RedBend’s web site, it seems not.

I can only repeat my old recommendation: Take a good OS course, guys! Such as the Advanced Operating Systems course I teach at UNSW. There you’ll not only learn the concepts, you’ll also learn how to design and implement kernels so they perform without shortcuts.

At last week’s VMworld, VMware presented, once more, their Mobile Virtualization Platform (MVP), now called Horizon Mobile. Besides the usual hype, there were a few things that I found somewhat annoying.

Specifically, VMware’s Raj Mallempati is quoted as saying: “What VMware is going to do is provide me a corporate phone, which is a virtual machine that is completely encrypted, completely managed and secure, and they are going to deliver that onto my device.”

Even considering that it is coming from a marketing guy, I find this statement rather dishonest. Because secure it ain’t. Not for the business. Not for the owner of the phone.

Let me explain.

Insecure for the business

As I explained in a blog last year, VMware’s hypervisor is hosted inside the phone’s native Android OS kernel (which is why they call it, incorrectly, a Type-2 hypervisor). What this means is that whoever owns that OS kernel owns the VMware hypervisor, and thus the virtual machine which contains the business phone. They encrypt the business phone’s data on flash, but that doesn’t provide any protection if the native Android kernel is compromised, it can simply read the keys out of memory.

Hence, if an app compromises the Android kernel, it controls the business phone, including all its data, network connections, the lot. And notice that the private phone keeps functioning as normal, meaning the owner is free to install and run any arbitrary Android app. With the Android kernel comprising about a million of lines of code, it can be expected to contain about 10,000 bugs. How many of the 100,000+ Android apps trigger an exploit? Probably plenty. In fact, this is the primary reason businesses don’t like company-provided handsets to be open, they fear security to be compromised.

Insecure for the owner

But the setup isn’t secure for the phone’s owner either. It would be if VMware used a proper Type-2 hypervisor, as that would be completely untrusted from the native Android kernel’s point of view. However, as I explained in another blog last year, the MVP setup is actually neither a Type-1 nor a Type-2, but a hybrid hypervisor. It is hosted inside the host OS, not on top of it. (They wouldn’t be able to achieve acceptable performance with a Type-2.)

What this means is that VMware essentially installs a rootkit into your Android kernel, which re-directs the exception vectors to their hypervisor module. Meaning they take over your phone. Effectively, your phone is now “owned” by whoever controls the hypervisor. Which isn’t you, the owner, it’s VMware or the OEM or the network provider or your employer (or maybe all of them). All your private data is at their mercy.

And VMware go on to say that they combine this with device management software, so they can remotely wipe the phone without touching it. Only the business phone, of course. Really? Are they going to cleanly un-install the rootkit? If you just got fired, would you trust your former company with all your private data? In fact, would you trust your company with all your private data on the phone even while you’re still working for them?

Summary: It Ain’t Secure!

Not secure for the company, not secure for the phone owner. Take my Advanced OS class, guys!

Recently I had a look at what has become of VMware’s MVP and explained the security shortcomings of the Type-2 hypervisor design. Today I’m looking at VWware’s approach in more detail, and explain why it is in fact not a real Type-2 hypervisor, and what this implies.

Type-2 hypervisors are known for poor performance. The reason I had explained in detail a while back, I’ll summarise them here (refer to the earlier blog for more details).

A system call performed by an application is a privileged operation which is intercepted by the hypervisor, which (after deciding that this is an operation which should be handled by the guest) forwards it to the guest OS. The return to user mode from the guest takes a similar detour through the hypervisor, as indicated in the left part of the diagram.

In the case of a Type-1 hypervisor, this results in a total of four mode switches and two context switches. However, in the case of a Type-2 hypervisor, the system call is trapped by the host OS, which delivers it to the hypervisor, and a return from the hypervisor to either the guest or the app similarly takes a detour via the host. All up, the number of mode switches and context switches is doubled, as indicated in the right part of the diagram. Further cost arises from the fact that while a Type-1 hypervisor (such as OKL4) is highly optimised for this trampolining, the host OS generally isn’t. In reality, the overhead of doing a simple system call is in the Type-2 case not just double that of the Type-1, but closer to an order of magnitude higher. This is why virtualization with a Type-2 hypervisor is generally slow. Note that ARM’s forthcoming architecture extensions to support virtualization (I’ll discuss them in a future blog) help to reduce the overheads of a Type-1 hypervisor, but do little to help a Type-2.

VMware understands this, and has taken a different approach in MVP, which I’ll explain now.

Fundamentally, the high cost of Type-2 virtualization stems from the fact that the hypervisor effectively consists of two parts, the host OS and the hypervisor proper, that each (logical) hypervisor invocation bounces twice between those layers, and that the host mechanisms used for this bouncing are inefficient. So, what VMware does in MVP is to merge the hypervsior back in with the host.

This is done by loading a MVP module (called “MVPkm”) into the host OS kernel, as shown in the diagram to the right. (They discuss this for Android, it is not clear whether they plan to support other hosts, such as Windows or Symbian. If they do, they’ll have to redo the kernel module for each host.) The MVP module effectively hijacks the host, by re-writing the exception vectors, so it obtains control whenever the guest kernel is entered. (Note: this is exactly what a piece of malware would do.) The process turns the host kernel into a hypervisor.

The result is not really a Type-2 hypervisor any more, as it actually runs native, not on top of a host OS (but inside) and has direct control over physical resources (rather than the virtualized resources provided to it by the host). However, it it isn’t a Type-1 hypervisor either, as it does not have exclusive control over the hardware, this is shared with the rest of the host, and any code inside the host kernel can interfere with the operation of the hypervisor module.

So, if this hypervisor is neither a Type-2 nor a Type-1, what is it? I call it a hybrid hypervisor, as it is somewhat of a blend of the two basic types. A better-known representative of the hybrid hypervisor type is the widely-used KVM (often falsely referred to as a Type-2 hypervisor). It operates very similarly, although KVM is dependent on virtualizaiton extensions to the architecture (MVP is not, but can make use of them).

The hybrid hypervisor can achieve similar performance as a Type-1 hypervisor, so this scheme seems pretty neat at first glance. The problem is that this performance is bought at a heavy price.

The one advantage a Type-2 hypervisor has over a Type-1 is that it can be easily installed: for the host OS it’s just another app, and it is installed just like an app, without requiring any special privileges.

This advantage is lost with the hybrid approach. It requires inserting a kernel module into the host OS, which is a highly security-critical operation (after all, it is the same as installing a root kit into the kernel!) As such it requires special privileges. On a mobile phone it requires cooperation with the device vendor or network operator, as they try very hard to prevent the unauthorised insertion of malware-like code into the OS!

While losing the ease-of-install advantage of the Type-2 to buy Type-1-like performance, the hybrid hypervisor inherits all the other drawbacks of the Type-2 hypervisor, especially the huge size of the trusted computing base. Everything in the host OS (all of a million or so lines of code!) needs to be trusted, a huge attack surface. So, while MVP is a hybrid hypervisor rather than a real Type-2, everything about the drawbacks of VMware’s approach I discussed in the earlier blog and its successor remains valid!

In summary, the hybrid approach taken with MVP has no discernible advantage over a lightweight, high-performance Type-1 hypervisor such as OKL4. MVP still requires manufacturer/MNO cooperation to install (unlike a real Type-2). It can, in theory, reach the performance of OKL4, although I’ll believe that when I see it, given that OKL4’s performance is so much better than anything else I’ve seen. But the fundamental weakness of the hybrid approach, which it shares with proper Type-2 hypervisors, is that it adds nothing to security of the guest apps, they are every bit as exposed as if they were running directly on the host. Which begs the question: Why bother?

Speaking of attacks, if you think carefully about it, you realise that MVP might very well increase the exposure of handsets to malware. Put yourselves in the shoes of a blackhat and think about how to get a rootkit onto a handset. If you know that a handset is provisioned to have MVP loaded on it, you know that it has provision for loading the MVP kernel module. It might well be that the easiest way to crack the system is to write a rootkit module which masquerades as MVPkm. I’ll sure stay away from such phones!

In a future blog I will investigate how each type of hypervisor does (or doesn’t) support the various use cases for mobile virtualization. Stay tuned, and drop me a line if you have questions.

Last week I talked about the backwards step VMware is taking by implementing their long-overdue mobile virtualization platform (MVP) as a Type-2 hypervisor. In the meantime, an insightful blog (which liberally quotes from my blog, although without attribution) talks about their use of encryption to try to protect user (actually, enterprise) data. I’ll explain here why this is just window-dressing, providing an appearance of security rather than the real thing.

VMware say they encrypt the guest’s data on flash and also use an encrypted VPN tunnel to connect to the enterprise network. Surely, this will protect the data from attacks?

Surely not. This is akin to thinking that the data on your Windows laptop is safe from rootkits because the disk is encrypted. It ain’t. Where encrypting the disk helps is if you lose your laptop and someone finds/steals it and breaks into it. If your OS gets infected by malware, it helps zilch. ‘Cause in order to be processed, the data is loaded into memory and decrypted. And there it is fully accessible by the OS, and if that OS is infected, there’s no way to stop the malware from seeing (and leaking) your data.

Same story on the phone with the Type-2 hypervisor. The hypervisor can encrypt the guest’s data until the cows come home, that doesn’t protect it from malware infecting the hypervisor or the host OS underneath. If the host gets cracked, the hypervsior gets cracked. If the hypervisor gets cracked, you lose. No way around this fundamental truth. And the inconvenient bit of the truth is that the host+Type-2 presents a huge attack surface. While for a well-designed Type-1 hypervisor, such as the OKL4 Microvisor, that attack surface is tiny, about two orders of magnitude smaller. Take your pick!

So, what is an MVP-style solution good for? I’ll look at this later, but first need to take a more in-depth (and rather technical) look at VMware’s approach. Stay tuned!

VMware has finally lifted the lid on their long-promised mobile virtualization platform (MVP). And, surprise, it’s a Type-2 hypervisor! This is a bit of a let-down, and has some interesting implications on what MVP can (or rather cannot) do, which I’m going to explore in a few blogs.

First a bit of background. Observers of the mobile virtualization space will remember that about two years ago, VMware, better known for server and desktop virtualization products, bought our then competitor Trango. At the time they promised MVP-based products “should arrive in around 12 to 18 months“. That’s phones with MVP on it. Almost 24 months later, there isn’t even a product announcement for MVP. It’s been a bit like waiting for Godot…

In the meantime, the OKL4 Microvisor has been around for yonks. It’s available, it’s benchmarkable, it’s being deployed—it’s real. And, as befits something with “L4” in the name, it defines the state of the art of hypervisors for embedded systems.

Well, at last (least?) VMware presented their vision, accompanied by a demo, at a BOF at last week’s OSDI conference in Vancouver. Not exactly a high-profile announcement. And it’s a Type-2 hypervisor!

I’ve discussed Type-1 vs Type-2 in a blog a year ago, and another one a few months earlier, and will probably explore this topic a bit more in a future blog. For now I’ll focus on what VMware is trying to sell, and why it doesn’t actually doesn’t solve the problem they claim they are addressing. Further technical discussion will look at why they taking this particular stance. (Hint: If all you’ve got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Even an egg…)

Hypervisors (also called virtual machine monitors) are designed to provide multiple virtual machines which can each run an OS with all of its apps. The fundamental difference between a Type-1 hypervisor (such as OKL4) and a Type-2 is that the former runs on bare metal, between the hardware and the operating system(s). In contrast, a Type-2 hypervisor runs on top of an OS (which is why it’s also called a “hosted” hypervisor).

That difference is much more significant than it may seem. It implies a completely different relationship between the hypervisor and the various operating systems. With Type-1, the hypervisor is master, it controls the OSes (called “guests”). With Type-2, the master is an OS (the one which hosts the hypervisor), it controls the hypervisor, which can only control the other OSes. Keep this in mind.

So, what problems is VMware (pretending) to solve with their Type-2 hypervisor? The main use case they are highlighting is BYOD, “bring your own device”. (Yes, they adopted the terminology we introduced 18 Months ago—good on them!)

The motivation for BYOD is that smartphones have business as well as private use. People like to control their private phones: They want to decide on the type and model, and they want to install their choice of apps. In contrast, companies like control over the phones used for business: They want to decide the model (ideally a single one for everybody) and what software runs on them. This forces an increasing number of people to carry two phones, business and private.

The idea of BYOD is that a single phone can serve both purposes: a person buys a phone of their choice, takes it to their company’s IT dudes, and they install a virtual business phone on the BYOD handset. Sounds great, doesn’t it?

The devil is in the detail, and it’s those details which make MVP a non-solution.

Why do companies want control over the phone? There’s only one reason: security. The whole point of issuing smartphones to employees is to keep them linked into the enterprise IT infrastructure while they are on the move. Traditionally this is all about email, address books and calendars, but increasingly it is a much deeper integration, enabling the phone to access employee records, sales databases, engineering designs—anything you’d access from your computer screen in the office.

So, the bottom line is that companies are worried about the security and integrity of their data when accessed via the mobile device (phone, tablet or whatever it might be). They are worried that accessing this critical data from an uncontrolled phone puts the critical enterprise information at risk. And they are right: phones do get infected by malware, and with each application installed, the risk of infection increases. This is the core challenge BYOD must address.

Surely, VMware understands this? Maybe they do, but if so, why do they offer solution which doesn’t cut the mustard?

The reason I say this is that the BYOD model VMware is propagating does nothing to solve this fundamental security issue, while OKL4 does.

This is illustrated in the figures at the left. With OKL4, the (Type-1) hypervisor is in control of all hardware. It isolates the VMs and their OSes from each other. If the user gets their private OS infected, that’s tough for them, but the infection cannot spread across VMs to the business environment. In order to subvert this, the attacker either has to have already subverted some of the enterprise IT infrastructure (thus coming in from the business side into the business OS) or has to attack the hypervisor from the private VM. But the hypervisor has an extremely small attack surface! The hypervisor is very small (about 10,000 lines of code). Technically speaking, the business VM has a small trusted computing base (TCB).

In VMware’s Type-2 model, it’s quite different. The business environment is controlled by the hypervisor, which is controlled by the host OS (the one that comes with the BYOD phone). If this gets cracked, as it inevitably will be, then it’s trivial to crack the hypervisor, and then you control the business OS! The reason this is easy to crack is that in this setup, the business OS has a huge TCB. It includes the complete private OS, which likely comprises upwards of 1,000,000 lines of code—two orders of magnitude more than OKL4!

Now remember where we’re coming from. The original motivation for BYOD was that companies don’t trust people’s private phones with critical business data, because these phones get cracked, which would compromise the business data. The idea of BYOD, as promoted by OK Labs, is to provide a virtual business phone on the private handset which is just as secure as if it was a physically separate handset.

If you followed my argumentation above, you’ll see that VMware’s solution is no bit more secure than allowing people to access the business data through their normal private phones, without the detour via a hypervisor. In other words, MVP adds nothing to security. So why would you pay for it then? You might as well cut out the middle man and allow people to access the enterprise IT system from their unmodified private phones. Security-wise, there is no difference whatsoever.

At OK Labs, we believe that security isn’t something that’s solved with PR. It requires a technically-sound approach. It requires a minimal TCB. It requires OKL4.

Stay tuned for a more in-depth look at these issues.

System virtualization is increasingly being used in embedded systems for a variety of reasons, mostly anticipated in a paper I wrote last year. However, the most visible use case is probably still processor consolidation, as exemplified by our Motorola Evoke deployment. Given that the incremental cost of a processor core is shrinking, and likely to go to zero, this makes some people think that the use of hypervisors in embedded systems is a temporary phenomenon, which will become obsolete as multicore technology becomes the standard. These people are quite wrong: in embedded systems, multicore chips will depend on efficient hypervisors for effective resource management.

In order to explain this prediction, let’s look at a few trends:

- Embedded systems, particularly but not only in the mobile wireless space, tend to run multiple operating systems to support the requirements of different subsystems. Typically this is a low-level real-time environment supported by an RTOS, and a high-level application environment supported by a “rich OS”, such as Linux, Symbian, or Windows. This OS diversity will not go away, it will become universal.

- Energy is a valuable resource on mobile devices and must be managed effectively. Key to energy management is to provide the right amount of hardware resources, not more, not less. The most effective way of reducing energy consumption on a multicore is to shut down idle cores—the gain far exceeds that possible by other means such as dynamic voltage and frequency scaling (DVFS). This gap will become more pronounced in the future: on the one hand, shrinking core voltage squeezes the energy-savings potential of DVFS, while on the other hand, increasing number of cores mean that the energy-saving potential of shutting down cores increases while becoming at the same time a more fine-granular mechanism.

- Increasing numbers of cores on the SoC will encourage designs where particular subsystems or functionalities are given their own core (or cores). Some of these functions (e.g. media processors) will use a core in an essentially binary fashion: full throttle or not at all. These are easy to manage. However, other functions impose a varying load, ranging from a share of a single core to saturating multiple cores. Managing energy for such functions is much harder.

Because of point (2), (3) is best addressed by allocating shares of cores to functions (where a share can be anything from a small fraction of one to a small integer). Sounds like a simple time-sharing issue: you have a bunch of cores and you share them on demand between apps, turning off the ones you don’t need. Classical OS job, right?

Yes, but there’s a catch. Multiple, in fact.

For one, existing OSes aren’t very good at resource management. In fact, they are quite hopeless in many respects. If OSes did a decent job at resource management, virtualization in the server space would be mostly a non-event (in the server space, virtualization is mostly used for resource management). Embedded OSes aren’t better at this than server OSes (if anything they are probably worse).

Now combine this with point (1) above, and you’ll see that the problem goes beyond what the individual OS can do (even if the vendors actually fixed them, which isn’t going to happen in a hurry). In order to manage energy effectively, it is possible to allocate shares of the same core to functionality supported by different OSes.

Say you have a real-time subsystem (your 5G modem stack) that requires two cores when load is high, but never more than 0.2 cores during periods of low load. And say you have your multimedia stack which requires up to four cores at full load, and zero if no media is displayed. And you have a GUI stack that uses between half and two cores while user interaction takes place (zero when there’s none). Clearly, while the user is just wading through menus, only about 2/3 of the power of one core is required, but there are still two OSes involved. Without virtualization, you’ll need to run two cores, each at half power or less. With virtualization, you can do everything on a single core, and the overall energy use of the single core running at 2/3 of its power will be less than the combined energy gobbled up by two cores running on low throttle. (And on top you have the usual isolation requirements that make virtualization attractive on a single core.)

In a nutshell, the growing hardware and software complexity, combined with the need to minimise energy consumption, creates a challenge which isn’t going to be resolved inside the OS. It requires an indirection layer, which is provided by a hypervisor. The hypervisor maps physical resources (physical cores) to virtual resources (logical processors seen by the guest OSes). This not only makes it easy to add or remove physical resources to particular subsystems (something OSes are notoriously bad at dealing with), but can further consolidate the complete system onto a single core, shared by multiple OSes, when demand is low.

How about heterogeneous multicores? I’ll leave this as an exercise for the reader 😉

A while back I discussed how one of our competitors (in an article which is great entertainment material for all the stuff it gets wrong), had falsely claimed that OKL4 was a Type-2 hypervisor. The Type-1 vs 2 issue has since come up a few times in different contexts, and there seems to be a bit confusion out there. So let me explain why no-one in their right mind would consider using a Type-2 hypervisor in a mobile phone.

A Type-2 hypervsior runs as a normal application on top of a normal OS, which is why it’s also called a hosted hypervsior. This is great for PCs, as it allows you, for example, to run Linux or Windows inside an application on a Mac, getting a bit of the best of two worlds. To a degree, at least. Anyone who does this (for example I run Linux on VMware Fusion on a Mac) will not fail to notice that some things are clearly much slower than they are on native Linux, or even on Linux running inside a virtual machine on a Type-1 (or bare metal) hypervisor. In fact, while performance differences between native Linux and Linux running in a Type-1 virtual machine is barely noticeable, the performance degradation on a hosted hypervisor is definitely significant.

The reason is simple: with a hosted hypervisor, you need to go through many more layers of software. For one, the inherent virtualization cost is at least doubled. A syscall on a natively running OS inherently costs two mode switches. Virtualized on a bare-metal hypervisor this becomes four mode switches and two context switches. On a hosted hypervsior this blows out to eight mode switches and four context switches. All that for only getting in and out of the guest kernel. My earlier blog has a more detailed explanation.

But a much bigger impact on performance has the fact that in a Type-2 scenario, the underlying OS effectively becomes part of the hypervsior, and it isn’t designed for that. Anyone who ever played with user-mode Linux (UML), which is a Type-1 scenario but using the general-purpose Linux kernel as the hypervisor, will confirm this. The performance just isn’t competitive, besides special hacks having been made to Linux to make UML more efficient. So, the bottom line is that Type-2 hypervisors simply can’t compete with Type-1 hypervisors in performance.

So, why would anyone in their right mind use one for mobile phones? Beats me. If you look at the typical use cases for virtualization in mobile wirless devices, you’ll see that in many of them a hosted hypervisor is simply not suitale at all. In the cases where a hosted hypervisor could be used, it has no compelling advantage over a native hypervisor, but a compelling performance disadvantage. Let’s look at the mobile virtualisation use cases:

- Processor consolidation: now way Jose. In the typical rich-OS + RTOS scenario, are you going to host the hypervsior on the RTOS? Most of them don’t even support memory protection, leave alone support for virtualization! Or host the hypervisor on the rich OS, running the RTOS on top? Clearly you’d lose the real-time properties for which you have the RTOS in the first place

- License separation, especially of GPL code: won’t help you with re-using Linux drivers, and will defeat most of the purpose

- Security: yes, a hosted hypervisor will preovide encapsulation, although at a much higher cost than with a native hypervisor, so why bother?

- Architectural abstraction: yes, but only if the underlying host OS plays ball. Again, cut out the middleman and you’ve got a winner.

- Resource-management for upcoming manycores: you lose with a hosted hypervisor, it buys you nothing there.

- Multiple user-environments (private and enterprise) and BYOD? Trying to do this with a hosted hypervsior would degrade at least one of the envrionments to second-class citizen status. Not only performance-wise, but also security wise: the primary environment (which is hosting the hypervisor which supports the secondary environment) is in control of resources. This means that it would be the one the enterprise IT folks would trust and need to control. And the complete BYOD idea goes right out of the window. Clearly a non-starter.

- The same can be said about other appraoches to using the phone as a terminal to access the enterprise IT infrastructure: Trying to do this in a hosted VM means you need to trust the host OS. The whole point is you don’t want to do this.

See what I mean? For All the use cases people talk about, a Type-2 hypervisor is either totally unsuited, or is a clearly second-rate solution compared to a Type-1 hypervisor. No-one with half a clue would want to do this. If you can think of reasonable use cases for hosted VMs, you’ll find that they are adequately supported by Java. Except that using a JVM allows a much leaner solution than a Type-2 hypervisor running on a rich OS.

You’ll likely get better mileage by using Java than an Type-2 hypervisor. But the Type-1 hypervisor is clearly the way to do. This is what OK does, competitor FUD notwithstanding.

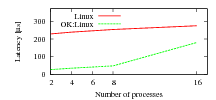

My Evoke white paper has triggered an unusual amount of comments, all to do with the brief discussion of fast context-switching and the graph reproduced here.

However, the unusually large number of comments and queries tells me that I should provide a bit more explanation. Here we go (although it can really all be found in the referenced publications too…)

The graph shows that context-switching costs in OK:Linux are significantly lower than in native Linux on an ARM9 platform, but the gap narrows as the number of processes exceeds 8, and the graph ends at 16. And I said that “the improvement is particularly large if the number of presently active processes is small—a typical situation for mobile phones.”

First, I have to admit I was a bit sloppy when talking about “active processes”, many people (not unreasonably) interpreted to refer to the total number of non-zombie processes in the system. I should have used the technically accurate formulation “process working set”, but didn’t want to get too technical. Clearly, you should never be sloppy…

What does the “process working set” mean? The working set is a technical term in operating systems referring to the subset of a particular resource that is in active use over a certain (small) window of time. It can be applied to main memory, cache memory, processes or others. In this case the “process working set” is the set of processes which execute on the CPU in a particular, small, time window.

How small is “small”? That depends (and I remember that as a student I was frustrated that the prof didn’t provide a good answer to that question). Given the numbers we are talking about here (order of 10 processes, and order of 0.25ms overhead in native Linux) it makes sense to look at a few miliseconds. Given that the default time slice of Linux is 10ms, let’s say we’re looking at a window of a single time slice.

So, how big is the process working set in a typical (embedded) Linux system? Small. Remember, as long as a running process doesn’t block (waiting on a resource, such as I/O or a lock) or is preempted (as a result of an interrupt) it will execute for its full time slice. The working set size in this case is one. On my Linux laptop there are at any time at least 200 processes, but almost all of those are blocked waiting for some event (such as standard input or a mouse click). The number of processes running during a time slice will be small, I’d say it’s less than ten almost all the time. On a phone it’s likely to be less than on my laptop. Phones are becoming more and more like laptops, but they really aren’t doing as much as a typical laptop with dozens of windows and all those background processes our highly-bloated desktop environments are running.

So, I clearly stand by my claim, disputed by some, that the process working set on a phone is typically small, and normally much less than ten. Which implies that the context-switching overhead of OK:Linux is about an order of magnitude less than that of native Linux.

What if it does get bigger occasionally? The graph ended at 16, does that mean OK:Linux cannot have more than 16 processes in the working set?

Nope, there is no such limitation. OK:Linux supports as many processes as native Linux does, no matter how many of them form the working set.

Those of you who have read the FASS papers (referenced by the white paper) will know that our fast context switching is based on the use of a feature of the ARM9 MMU called “domains”, and there are only 16 of them (and one is reserved for kernel use, so there are 15 available). So, what if we have more than 15 processes? Well, we do what any decent OS does if it runs out of a resource: it recycles. So, we use “domain preemption” to share a limited number of domains among a greater number of processes. That has a cost, but it’s still better than not using domains at all, as the graph also shows: With 16 processes the latency is still only about 2/3 of that of native Linux. Once the process working set size gets really large, OK:Linux overheads end up a bit higher than those of native Linux. But I’ve never seen a mobile system with such a large process working set (remember, my busy laptop doesn’t even get there, how would a phone?)

But, of course, you don’t have to believe me, you can see for yourself. Check out the Evoke and its snappy UI, and tell me whether you’ve seen a phone with similar functionality, running on an ARM9 processor (even a dedicated one) that does better!

A few weeks ago I was talking to an engineer who had led the team that designed and built a recently-released OKL4-based mobile phone. Among the technical details, one comment stuck in my mind: “There were no bugs,” he said, and his face had the expression of “… and I still find that hard to believe!”

This may sound incredible, but it’s true. Through the several years they worked with OKL4, they never triggered a bug in our code. Not a single one!

There are two observations that can be drawn from this.

Firstly this is clearly a compliment to our engineering team, reflecting well on our engineers, but also the maturity of our software process. If we release something, it works. Despite the rapid development the system has gone through, with significant changes to the API. You won’t find many companies which can do this. You need true world-class engineering.

The second is a reflection on the fundamental approach taken with OKL4: a small (well-designed) code base that minimises the part that executes in privileged mode. This is not only good for the robustness and security of the deployed code (the usual argument for a small trusted computing base). It’s also a massive help for our own software process: a bug in the privileged code can manifest itself anywhere, inside or outside the kernel. That’s part of the reason why kernel code is so much harder to debug than user-mode code. Keeping it small makes debugging easier, and thus increases engineering productivity, and overall product quality.

Of course, assembler code is even harder to debug than the same number of lines of C code. Which is the reason that we are constantly reducing the amount of assembler code in the kernel, without sacrificing performance. Compare that to products which proudly state that their kernel is completely written in assembler. Imagine how expensive and error-prone it is for them to change anything in the system? They’ll find it hard to react to customer requirements.

This is the fourth (and hopefully last) installment of my dissection of a paper our competitors at VirtualLogix had written and presented at IEEE CCNC last January. The paper compares what the authors call the “hypervisor” and “micro-kernel” approaches to virtualization.

In the previous blogs I explained how their flawed benchmarking approach makes their results worthless, that their idea of a microkernel represents a 1980’s view that has been superseded more than 15 years ago and gave specific examples of this. Now I’ll look at what they say about virtualisation and hypervisors, which, as it turns out is similarly non-sensical.

Their explanation of virtualization approaches starts off with somewhat amusing statements, when they say that for pure virtualization (i.e. without modifying the guest OS) you either need hardware support that’s only available on the latest processors or need use binary translation. That will come as a surprise to the folks at IBM who’ve done pure virtualization without binary translation for 40+ years…

What they apparently mean (but fail to say) is that many recent processors were not trap-and-emulate virtualizable and therefore require either of the above.

Much more concerning is that they present OKL4 as a Type-II (aka “hosted”) hypervisor — these are generally reputed to perform poorly compared to Type-I (aka. bare-metal) hypervisors, so the reader is at this stage primed to expect poor performance from OKL4.

This is quite misleading. A Type-II hypervisor runs as an application program on top of a full-blown OS. The virtual machine runs on top of that, and the Type-II hypervisor intercepts the VM’s attempts to perform privileged operations — typically by using the host OS’s debugging API — an expensive process. A Type-I hypervisor, in contrast, runs on the bare hardware.

A critical difference is in the number of mode switches and context switches required to virtualise an operation performed by the virtual machine. Say the app running in the virtual machine (let’s call it the guest app) is executing a system call, which causes a traps into privileged mode. This is shown in the figure below.

In the Type-I case, the syscall invokes the hypervisor. The hypervisor examines the trap cause, finds that it was a syscall meant for the guest, and invokes the guest’s trap handler. The guest delivers the service and executes a return-from-exception instruction (in the case of pure virtualization) or an explicit hypercall (in the case of para-virtualization). In each case, the hypervisor is entered again to restore the guest app’s state. In total this requires four mode switches (app-hypervisor-guest-hypervisor-app) and two switches of addressing context (app-guest-app).

In the Type-II case, the trap invokes the host OS. It notices that a “debugger” (the hypervisor) has registered a callback for syscalls, so it invokes the hypervisor. This one knows that this is an event for the guest OS, so it asks the host OS (via a syscall) to transfer control to the guest. The guest delivers the service and attempts to return to its app. This again traps into the host, which invokes the hypervisor, which invokes the host to return to the app. In total, 8 mode switches (app-host-hypervisor-host-guest-host-hypervisor-host-app) and 4 context switches (app-hypervisor-guest-hypervisor-app). Obviously much more expensive.

So, how does that compare to virtualization using OKL4? This is what happens if an OK Linux app performs a system call: The app causes a trap, which invokes the OKL4 kernel. It notices that this is not a valid system call, so it considers it an exception, which is handled by sending an exception IPC to the app’s exception handler thread. This happens to be the “syscall thread” in the OKL Linux server. OK Linux delivers the service, and invokes the OKL4 kernel to return to the app. In total, 4 mode switches (app-OKL4-Linux-OKL4-app) and 2 context switches (app-Linux-app).

Does this sound like a Type-II hypervisor? You’ll note that the expensive operations which determine the virtualization overheads (mode changes and context switches) are exactly those of a Type-I hypervisor. And the statement made in the paper that “the result of implementing virtualization on a micro-kernel host is a level of complexity similar to fully hosted VMs with high performance impact”? I think you’ll agree with me that this is utter nonsense.

Then there’s a truly stunning statement: “The micro-kernel is involved in every memory-context switch and the guest OS must be heavily modified to allow this.” The non-expert reader will be excused for interpreting this statement as implying that a “hypervisor” doesn’t have to be involved in every context switch. How is that possible? A context switch is clearly a privileged operation, as it changes access rights to physical memory. The hypervisor (and this is consistent with the definition given in the VirtualLogix paper) must have ultimate control over physical resources, and thus must be involved in each context switch.

Anyone who doubts this clearly doesn’t understand virtualization. So, this is an interesting statement from a virtualization provider. Folks, you really should take UNSW’s Advanced OS course! (Note that it would be possible to build hardware that knows about multiple user contexts, and can switch between them in certain situations without software interaction. But no ARM processor has such hardware.)

Finally, there’s the claim that for para-virtualizing a guest, the “microkernel approach” (read “OKL4”) requires more modifications than the “hypervisor approach” (read “VLX”). And this is supported by another apples-vs-oranges comparison: It is stated that to para-virtualize Linux 2.6.13 on a particular ARM platform for VLX required changes to 51 files and adding 40, while OK Linux “required” a new architecture tree which includes 202 new files, 108 of them ARM specific.

What they fail to mention is that this is a (well-documented) design choice of OK Linux. When para-virtualizing Linux, we chose to make the para-virtualization as independent of the processor architecture as possible. Hence we decided to introduce a new L4 architecture, and port to that one, with most processor-specifics hidden by the microkernel. Therefore the comparison made in the paper cannot be considered fair. Fairer would be to compare the sum of changes required to maintain para-virtualized Linux on several architectures.

But this isn’t the full story either. Just counting “added files” is a poor (and unscientific) metric. How big are those files? Once the first port is done, how many of them will ever need changing as Linux evolves? Without addressing those (and similar) questions, this comparison is completely meaningless.

Finally (and worst of all), the authors fail to mention another rather relevant fact. OK Linux on ARM9 processor is somewhat special: it contains support for fast context switching, the trick we use to make para-virtualized Linux do context switches 1–2 orders of magnitude faster than native Linux, without sacrificing security. Obviously, this requires some code to support (a fair bit, in fact). I’m not aware of VLX supporting this feature. So, this is apples-vs-oranges again.

Now, remember my first blog in this series. There I noted that they used an ARM11 platform for the performance comparison, and I stated that OKL4 wasn’t at the time particularly optimised on that platform, but highly optimised on ARM9. So, isn’t it interesting that for comparing code changes they actually use the ARM9 version (which requires far more extensive support code for fast context switching)? Can this really be an accident?

It’s amazing, isn’t it? Discussing what’s wrong with that paper produced almost as much text as the paper itself (and I’ve ignored plenty of minor things). And I would expect any of my students to be able to do this sort of dissection. You’ll probably understand that I think the reviewers of that paper were totally out of their depth.

In sum, that paper is utterly worthless, and almost all conclusions drawn in it are totally wrong.